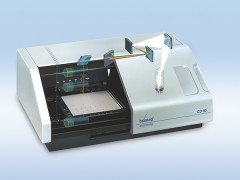

美国 BIOPAC 公司生产

特点:

★-无创、操作简便、连续的实时数据、波形显示;

★-波形与数据可本机打印输出;

★-也可以接入生理记录仪通过PC和显示器做到实时监测、波形数据保存、事后分析统计、Excel★-表格成档导出。 【详细说明】

Continuous non-invasive arterial pressure shows highaccuracy in comparison to invasive intra-arterial bloodpressure measurement I. INTRODUCTIonContinuous blood pressure (BP) monitoring is required ina multitude of clinical settings, especially in perioperativecare. For inpatient surgeries, the American Societyof Anesthesiologists (ASA) requires continuous perioperativeblood pressure monitoring at least for patients withsevere systemic disease; this necessitates the invasiveplacement of an intra-arterial catheter. In all other casesintermittent non-invasive blood pressure monitoring (NBP)is the standard of care. Therefore, the patients` bloodpressure may not be monitored at all times.A recent representative survey(1) among Austrian andGerman physicians (N=198) provides evidence that, in82% of inpatient surgeries, non-invasive blood pressuremonitoring is used. However, in 25% of these cases,especially in surgeries where hemodynamic instabilitiescan be expected or where aggressive management ofblood pressure might be required (e.g. in urologic, extendedlaparoscopic, orthopaedic or vascular surgeries, insurgeries in gynecology and obstetrics, in medium to extendedintestinal surgery and elective or urgent traumasurgery(2)), anesthetists would prefer a non-invasive continuousblood pressure monitoring to have better controlover the patient s hemodynamics. In the remaining 18%of inpatient surgeries, BP is measured continuously usinginvasive catheters (IBP), mainly in patients where cardiovascularinstability is expected and thus ASA guidelinesspecifically require continuous BP measurement and/orwhere repeated blood gas analysis is needed. Note that,in 26% of these cases the invasive catheter is insertedonly to enable continuous blood pressure monitoring.However, this is a time-consuming and cost-intensiveprocedure, causing pain for the patient and includingthe risk of infection, and thus should be replaced by anon-invasive method if possible.There are a number of studies stressing the importanceof continuous perioperative blood pressure monitoring:e.g., more than 20% of all hypotensive episodes duringsurgeries may be missed by intermittent upper-armblood pressure readings and another 20% may be detectedwith a delay(3). This in turn may prevent immediatetreatment or even lead to missing complete hypotensiveepisodes. It has been shown that intraoperativehypotension preceeds 56% of perioperative cardiacarrests(4) and is associated with a significant increase ofthe 1-year post surgical mortality rate(5), indicating thatintermittent NBP monitoring can be insufficient.Consequently, there seems to be a discrepancy betweenthe number of cases where continuous bloodpressure monitoring is needed and those cases whereit is actually used: Due to its invasive nature and associatedrisks, intra-arterial catheters can only be justified ina limited number of patients whereas anesthetists wouldlike to perform risk-free continuous BP monitoring in a greaternumber of cases. For exactly these situations CNAP has recently become available(6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). CNAP is designedfor anesthetists who look for more control in situationswhen continuous blood pressure is desirable, butthe risks and burden of an arterial line are not justified.CNAP provides continuous, non-invasive and risk-freebeat-to-beat blood pressure measurement.The aim of the present report was to evaluate the accuracyof CNAP in a real-life perioperative setting bycomparing simultaneous measurements of CNAP tocontinuous intra-arterial pressure monitoring.II. MethodsData recordingThe measurements were conducted in a perioperativesetting at the Department of Anesthesiology at LandeskrankenhausBruck an der Mur (Austria). In all patientsincluded in this report, continuous BP monitoring wasindicated by clinical safety standards. Arterial pressurewas measured simultaneously with an invasive catheter(Edwards Life Sciences Pressure Monitoring Set, Irvine,USA, connected to Datex Ohmeda S/5 monitor, GE, Helsinki,Finland) and the CNAP Monitor 500i (CNSystemsMedizintechnik AG, Graz, Austria) in fifteen patients undergoingorthopedic, cardiac and vascular surgeries(seven female and eight male patients, mean age of71 years, range 33 to 82 years, ASA classifications I-III: I in1 case, II in 12 cases, III in 2 cases). The arterial catheterwas placed ipsi-laterally (n=5) or contra-laterally (n=10)to the CNAP finger cuff in the A. radialis or A. brachialis,depending on indication and requirements. The surgerydurations averaged 1h39min with a minimum of 44minand a maximum of 3h01min, the total duration of recordingsobtained was approx. 25 hours.Data processingFrom the IBP as well as from the CNAP signal, systolic,diastolic and mean pressure values were derived foreach second. If one of the signals was missing (e.g. dueto transmission faults or artifacts) for one data point, allother measurements for that data point were consequentlydiscarded. Otherwise, no further data processingwas performed and a total of 75,485 data pointswere included into the statistical comparison.Sackl-Pietsch E., Department of Anesthesiology, Landeskrankenhaus Bruck an der Mur, AustriaData comparisonFor a comprehensive evaluation of CNAP , its underlyingmechanisms have to be considered: CNAP is anintegrated solution where relative BP changes are measuredat the finger sensor which are turned into absolutevalues based on initial readings from its integratedNBP-unit. This fact needs to be taken into considerationwhen comparing the blood pressure readings recordedby CNAP and IBP.Since three measurement positions are combined in thiscomparison (CNAP finger sensor, CNAP NBP-unit andIBP catheter), some physiological facts have to be takeninto account: namely, transformations of BP amplitudesand waveforms as illustrated in figure 1. This implies thata systematic offset between CNAP and IBP can be expected.Thus, it is not surprising that even the AAMI-SP10 standardrecommended by the FDA reports substantial differencesbetween indirect NBP and direct intra-arterialmeasurements(12). A meta-analysis with the results of ninestudies totaling 330 patients was performed which quantifiesthis systematic offset: The average differences betweenarterial and NBP-cuff systolic BP ranged from 0.8 to13.4 mmHg with standard deviations (SD) ranging from 0to 13.0 mmHg. Diastolic BP showed average differencesfrom 0.8 to 18.0 mmHg with SDs ranging from 0.0 to 10.2mmHg.This offset may be even magnified when IBP and NBPrecordings are taken on contra-lateral arms. Note that in10 out of the 15 patients reported on here, CNAP andIBP were placed on contra-lateral arms.Therefore, the following differences between CNAP and IBP can be expected:(i) Differences between the two BP waveforms.(ii) The characteristic offset between the absolute valuesof systolic, diastolic and mean pressure.Figure 1: Different blood pressure waveforms and amplitudes inthe (1) A. brachialis, (2) A. radialis and (3) A. digitalis, resultingin different systolic and diastolic valuesIII. RESULTSWaveform comparisonFigure 2 shows blood pressure waveforms recorded byCNAP compared directly to intra-arterial blood pressurewaveforms. The upper graph shows a short episodeof stable blood pressure. The bottom-up arrows indicaterising and the top-down arrows indicate falling BP rampsconsidered as results of volume status, the Frank-Starlingmechanism and autonomic regulation(13). The lower graphshows BP changes caused by perioperative treatmentor patient movement. Due to the fact that datawas recorded in the clinical routine, no further informationabout the patient`s treatment at this special timeslice is available. Nevertheless, the good accordance ofwaveforms indicates that CNAP can follow fast bloodpressure variations changes as well as IBP.Hemodynamic changesFor clinical application it is important to ensure thatCNAP is able to monitor fast hemodynamic changes.In figure 3 an example is displayed where short-term hemodynamicvariability during 25 minutes of orthopedicsurgery can be observed clearly: CNAP and IBP displaya parallel hemodynamic trend with the typical offsetbetween indirect and direct measurement methods.Sackl-Pietsch E., Department of Anesthesiology, Landeskrankenhaus Bruck an der Mur, Austria 2Continuous non-invasive arterial pressure shows high accuracy in comparison to invasive intra-arterialblood pressure measurementFigure 2: Blood pressure tracings showing the agreement ofCNAP (solid line) with IBP (dotted line) during anesthesia.Boxplots for all patients data setsFigure 4 shows boxplots for all 15 data sets, for meanBP values. This graph illustrates that most of the patientsshow a characteristic offset between CNAP and IBP.Bland-Altman-plots for the complete data setThe differences of CNAP and IBP data points werecomputed for every data point (n = 75,485) and plottedvs. their average, resulting in the Bland-Altman-plot ofFigure 5. No distinct trend of blood pressure differencein relation to the absolute mean values of pressure canbe detected, i.e. the diffe difference between the tworecording methods is the same over the whole range ofvalues.Furthermore, table 1 shows mean values and standarddeviations of differences of CNAP to IBP for systolic,mean and diastolic pressure for each patient separayas well as for the whole sample.Figure 3: Comparison of short-term trends of systolic, diastolicand mean blood pressure measurements from CNAP (solidlines) and from IBP (dotted lines) during 25 min of anesthesia.Figure 4: Boxplots of differences between CNAP and IBPvalues for all 15 patients (mean BP [mmHg]). The boxes containthe middle 50% of the data, the horizontal lines show themedian. The upper and lower edges of the boxes indicate the75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The 5-95% range of thedata is indicated by the ends of the vertical lines.Figure 5: Bland-Altman-plot of differences vs. average of alldata points (CNAP vs. IBP values, n=75,485) for mean BP[mmHg].Systolic BP Mean BP Diastolic BPpatient mean SD mean SD mean SD1 -10,03 13,83 4,29 9,87 8,80 6,802 2,56 7,54 16,09 5,82 19,24 5,883 -2,81 7,17 6,99 6,51 12,27 7,214 -7,82 12,06 1,88 12,62 9,94 14,115 1,31 6,63 14,41 5,88 20,25 4,706 -16,43 5,11 -9,44 4,15 -3,99 4,387 -1,33 8,00 5,44 6,15 14,46 5,078 -10,77 5,69 1,91 3,71 7,34 2,869 -11,20 7,78 -0,81 6,71 3,75 6,9110 -9,93 7,82 1,93 3,86 7,16 3,2211 -25,82 8,37 -7,48 4,62 0,22 3,8912 -1,45 6,95 6,52 7,73 10,95 6,4113 0,24 11,62 6,81 7,91 11,09 7,3414 33,55 4,59 32,00 7,10 37,77 5,7715 2,89 10,49 13,58 5,84 19,69 4,99Total -2,96 13,81 6,66 11,23 12,36 10,91TABLE 1: Means and standard deviations (SD) of differencesbetween CNAPTM and IBP [mmHg].Sackl-Pietsch E., Department of Anesthesiology, Landeskrankenhaus Bruck an der Mur, Austria 3Continuous non-invasive arterial pressure shows high accuracy in comparison to invasive intra-arterialblood pressure measurementIV. DISCUSSIonWithin an every day clinical setting, CNAP and IBP readingswere recorded simultaneously during inpatient surgeries.The results of this perioperative comparison indicatethat CNAP has a high usability during anestheticcare: the overall statistical analyses of systolic, mean anddiastolic blood pressure show small differences and standarddeviations between the two methods. The graphicalcomparison of BP waveforms and short-term trendsduring anesthesia indicates that CNAP can follow hemodynamicvariability as fast as IBP. These results givestrong support to a high accuracy of the non-invasiveCNAP device in comparison to the invasive measurement.The waveforms of CNAP and IBP shown in figure 2 complywell with the physiological expectations (see section Methods ).As can be seen, CNAP corresponds to the IBPsignal both in resting conditions as well as in movement.For perioperative usability of the CNAP system, it is essentialto show that CNAP can deal with hemodynamicchanges as well as IBP: The trends of systolic, diastolicand mean BP depicted in figure 3 show excellent visualaccordance between the two devices.To illustrate the overall agreement between CNAP andIBP, figures 4 and 5 sum up the results for all 15 patients.The validation of CNAP with a total observation durationof about 25 hours and 75,485 data points is very acceptable:The mean values and standard deviations ofdifferences to the intra-arterial recordings comply withthe results of the meta-analysis recommended by theFDA.As can be seen in figure 4, all patients have their owncharacteristic offset between CNAP and IBP. only patientno. 14 seems to slightly deviate from the rest with ahigher pressure difference which may be explained bythe patients arteries: in patient no. 14 the vessels weredescribed by the clinician as stiff and the IBP readingsas dependent on bedding , thus making the arterial referenceless reliable and the results surprisingly good. onthe other hand, not even in the case where a patient speripheral perfusion was described by the physicianas poor (patient no. 11) did the CNAP system fail toquickly find a suitable BP waveform and the results comparedto IBP are very satisfactory.The individual, physiologically-determined offset canalso be seen clearly in the cluster of data points of eachpatient in figure 5 (e.g., note patient no. 14 in the upperright-hand corner). Nevertheless, the Bland-Altman-plotbetween CNAP and IBP shows no distinct trend of meanpressure difference in relation to the average values ofpressure, i.e. the difference between the two recordingmethods is the same over the whole range of values. Thisindicates that CNAP measurement is reliable in normal,hypotensive and hypertensive episodes.The mean values and standard deviations of differencesbetween CNAP and IBP reported in table 1 confirm thefindings of the meta-analysis in the current ANSI standard.These results are very satisfactory considering the patientsample included in this report. Note that data was recordedin patients with severe systemic disease or duringhigher-risk surgeries where the placement of an invasivecatheter was motivated by safety considerations.Although the results of this report indicate a high clinicalusability of CNAP , some remarks have to be madeabout the comparison to IBP measurements: There iscommon agreement that true blood pressure is bestdetermined directly using a reliable, calibrated transducerin an artery. Nevertheless, there is also consensusthat the direct intra-arterial measurement is fraught withits inherent set of issues, including variability with radialposition, vasoconstriction, the effects of flow-velocitychanges and the frequency response of amplifier andtransducer. Taking this into account, the results of thispresent report are even more remarkable.V. ConclusionOn the whole, the reported results provide clear evidenceof an excellent clinical feasibility and high accuracyof the non-invasive BP measurement device CNAP in comparison to IBP.With intermittent measurement of oscillometric sphygmomanometers(NBP), short-term but clinically relevanthemodynamic changes during anesthesia are not satisfactorilydetectable. Therefore, the demand fromanesthetists for a system providing non-invasive, continuousbeat-to-beat BP is increasing.CNAP provides patient comfort and usability similar toa standard upper-arm NBP and clinical data shows thatits accuracy is comparable to IBP. Thus, CNAP is theconvenient solution for anesthetists who want to havecomprehensive hemodynamic control to ensure highestpatient safety.Sackl-Pietsch E., Department of Anesthesiology, Landeskrankenhaus Bruck an der Mur, Austria 4Continuous non-invasive arterial pressure shows high accuracy in comparison to invasive intra-arterialblood pressure measurementVI. REFERENCES1. von Skerst B: Market survey, N=198 physicians in Germanyand Austria, Dec.2007 - Mar 2008, InnoTech ConsultGmbH, Germany2. Ezekiel MR. Handbook of Anesthesiology. Current ClinicalStrategies Publishing. 20033. Dueck R, Jameson LC. Reliability of hypotension detectionwith noninvasive radial artery beat-to-beat versus upperarm cuff BP monitoring. Anesth Analg 2006, 102 Suppl: S104. Sprung J, Warner ME, Contreras ME et al. Predictors ofSurvival following Cardiac Arrest in Patients UndergoingNoncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2003; 99:259 695. Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Anesthetic managementand one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery.Anesth Analg. 2005 Jan;100(1):4-10.6. Fortin J, Gratze G, Wach P, Skrabal: Automated noninvasiveassessment of cardiovascular function, spectraanalysis and baroreceptor sensitivity for the diagnosisof syncopes. World Congress on Medical Physics andBiomedical Engineering. Med Biol Eng Comput, 35,Supplement I, 466 (1997).7. Gratze G, Fortin J, Holler A, Grasenick K, Pfurtscheller G,Wach P, Kotanko P, Skrabal F: A software package fornon-invasive, real time beat to beat monitoring of strokevolume, blood pressure, total peripheral resistance and forassessment of autonomic function. Comp in Bio Medicine;28, 121-142 (1998).8. Fortin J, Habenbacher W, Gruellenberger R, Wach P, SkrabalF: Real-time Monitor for hemodynamic beat-to-beatparameters and power spectra analysis of the biosignals.Proc. of the 20th Annual International Conference of theIEEE Eng in Medicine and Biology Society, 20, 1 (1998).9. Fortin J, Marte W, Gr llenberger R, Hacker A, HabenbacherW, Heller A, Wagner Ch, Wach P, Skrabal F: Continuousnon-invasive blood pressure monitoring using concentricallyinterlocking control loops. Computers in Biologyand Medicine 36 (2006) 941 95710. Fortin J, Alkan S, Wrede C E, Sackl-Pietsch E and Wach P:Continuous Non-invasive Arterial Pressure (CNAP ) AnInnovative Approach of the Vascular Unloading Technique.Submitted for publication in Blood Pressure April2008.11. Fortin J: Continuous Non-invasive Measurements of CardiovascularFunction. PhD-thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering,University of Technology Graz, 2007, pp. 103-21.12. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.American National Standard. Manual, electronic orautomated sphygmomanometers ANSI/AAMI SP10-2002/A1. 3330 Washington Boulevard, Suite 400, Arlington, VA22201-4598, USA: AAMI; 200313. Parati G, Omboni St, Frattola A, Di Rienzo M, Zanchetti A,Mancia G. Dynamic evaluation of the baroreflex in ambulantsubject. In: Blood pressure and heart rate variability,edited by di Rienzo et al. IOS Press, 1992, pp. 123-137.Sackl-Pietsch E., Department of Anesthesiology, Landeskrankenhaus Bruck an der Mur, Austria 5

手机版|

手机版|

二维码|

二维码|